Articles A Breman exhibit opening Aug. 14 celebrates JELF’s history from orphans to college students – 8-24-17

140 Years of Aiding Jewish Education

By TOVA NORMANAugust 8, 2017, 3:22 pm

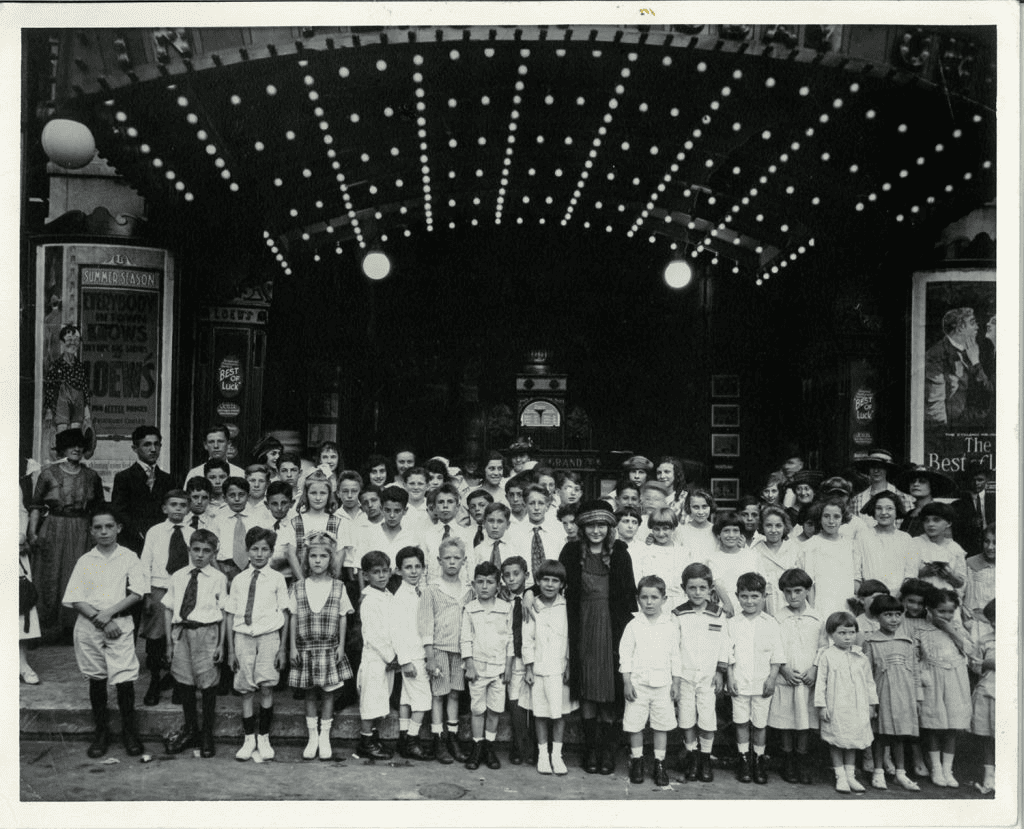

Photo from the Simon Scher Family Papers, Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History, Breman Museum Residents of the Hebrew Orphans’ Home take an outing to Loew’s Theater in Five Points around 1920. In the photograph are Isaac Ashendorf, Lena Buchwald, Sam Buchwald, Eva Cherry, Louis Cline, Madge Evans, Oscar Felsenstein (Fields), Sarah Franklin (Brisker), Aline Gable, Rose Goodman, Sam Goodman, Billy Grauer, Reuben Grauer, Clara Green (Kooperman), Danny Green, Edna Groh (Sears), Hilda Groh (Satterwaite), Jacob Groh, Alma Hankin (Keller), Ethel Hankin, Eugene Hankin, Viola Hankin, Martha (maybe Rose) Hirsch, Henry Hyman, Gussie Jackson, Esther Johnson, Stella/Estelle Johnson (Segal), Isaac Katz, Jacob Katz, Percy Katz, Rebecca Katz (Landsman), Napoleon (Poley) Kauffman, Robert (Skeeter) Lavenstein, Jean Myers (Spielhoz), Evelyn Myers (Poes), Abraham Nirenstein (Niren), Benjamin Nirenstein (Niren), Rose Nirenstein (Niren) (Kaplan), Yetta Nirenstein (Niren), Benjamin Oppenheimer, Benjamin Perloff, Sam Perloff, Lewis Perloff, John Henry Peyser, Harry Rippa, Gertie Rosen (Markowitz), Harry Rosen, Ida Rosen (Feinberg), Jack Rosen, Morris (Murray) Rosen, Sam Rosen, Sara Rosen, Bennie Rosenbaum, Esther Rosenthal (maybe Rosenblot), Clara Ruben, Fannie Scher (Arbesman), Rachel Scher, Simon Scher, Isadore Segal, Jacob Shain, Daniel Stein, Lincoln Stein, Rufus/Raphael Tarragon, Harry Whiteman, Lena Whiteman and Florence Wolfson.

For months, Jewish Educational Loan Fund CEO Jenna Leopold Shulman and colleagues and volunteers spent several hours a week reading through the archives at the Breman Museum.

The files chronicled the history of JELF and its predecessors: the Hebrew Orphans’ Home and Jewish Children’s Services.

In 1876, Simon Wolf, an influential businessman, submitted a resolution at the Grand Lodge Convention of B’nai B’rith’s 5th District to finance an orphanage for Jewish children. In 1889, with the help of Wolf and the Atlanta Jewish community, the Hebrew Orphans’ Asylum, later renamed the Hebrew Orphans’ Home, opened in Atlanta at 478 Washington St., half a mile from the state Capitol.

In the 1930s, it became Jewish Children’s Services, an adoption and foster care agency. Finally, in 1989, it became JELF, an organization providing interest-free loans to Jewish college students in Georgia, Florida, the Carolinas and Virginia.

The community can explore the rich history of JELF, the oldest nonprofit organization in the state of Georgia, at a new exhibit at the Breman: “The Legacy of the Hebrew Orphans’ Home: Educating the Jewish South Since 1876,” which opens Monday, Aug. 14, in the Blonder Gallery.

“We’ve always believed in helping people who are needy and giving them everything we could to get out of that cycle,” JELF CEO Jenna Leopold Shulman says.

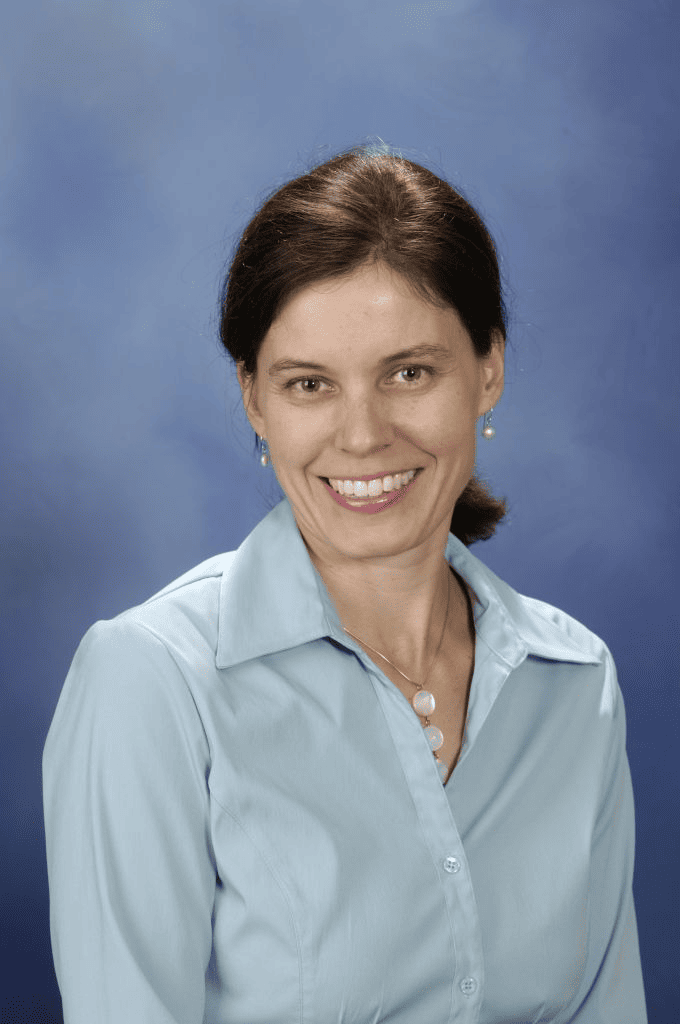

The exhibition was curated by Kennesaw State University history professor Catherine Lewis, the university’s assistant vice president of museums, archives and rare books and the director of its Museum of History and Holocaust Education.

Ghila Sanders, the acting director of the Breman, said the exhibit was a team effort.

“From the current JELF board and staff, to The Temple, Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta and the Breman Museum, and of course the curator, Catherine Lewis, and her team, everyone had a part,” she said.

Which is why Shulman and her cohorts were reading through the archives.

“There were times where I was so hooked on a file that I wouldn’t get up until I was finished,” said Shulman, who read the files of children and the minutes from board meetings. “To feel the old paper that things were written on and read the language that they used” showed the depth of the organization’s history.

She also saw similarities in issues she deals with: marketing and fundraising.

“In 1920 they were dealing with the same fundraising issue that we are dealing with today,” Shulman said.

That connection with the past made her feel more connected to her mission at JELF. “I feel even a deeper connection and responsibility to preserve the organization,” she said. “I feel like I’m contributing to its history right now.”

Bringing the archives to life is what the exhibit is about.

“Having an exhibition that features items from our archives is really about saving and interpreting the stories of real people through the artifacts and papers that were created in their daily struggles and accomplishments,” Sanders said. “Organizations like JELF affected and continue to affect people profoundly. To be able to bring those stories to the public, make history accessible, and create a connection between past, present and future is at the core of our work.”

In telling JELF’s story, Lewis explored what made the organization so resilient.

“That was really what I was trying to figure out: What was it about JELF that helped it survive?” she said.

Lewis pointed to good planning, strategic work and understanding of the changing landscape of what children needed. But she said there was one constant: “The thread that pulled through everything was education.”

Marianne Garber, the president of the JELF executive board, whose father-in-law, Al Garber, was raised in the Hebrew Orphans’ Home, agreed that education has been a consistent priority.

“Our organization realized early on that education was one of the four keys to success for the kids raised in the orphanage and later foster care,” she said. “Education was not only something they could give the children, but also a necessity for them to lead successful lives in the U.S.”

Sanders said the exhibition shows that even as JELF changed, the organization stayed committed to its original purpose.

Henry Birnbrey is speaking on the exhibit-opening panel to “express my gratitude and hope that people will realize the good a community can do.”

“The story of JELF is a story of acumen and flexibility, of an ambitious vision brought to life through an organization that never got old, adapting to the changing realities and changing needs of the community it was created to serve while staying true to its core mission,” she said.

That mission has always been about helping children in need, Shulman said.

“There is no doubt that the organization has always had kids’ and students’ interests at heart and that we’ve always believed in helping people who are needy and giving them everything we could to get out of that cycle,” she said. “When there is no one for them, we’re here for them.”

In curating the exhibit, Lewis saw the impact of JELF and its predecessors.

“To hear people over and over and over again say that an organization has helped them reach their goal or dream was really satisfying,” she said.

One of the people helped by JCS was Henry Birnbrey when he arrived in Atlanta after escaping the Nazis in 1938.

“They were sort of my counselors, advised me on which school to attend, took care of my wardrobe needs and transferred funds to my foster parent,” he said. “Periodically, I had sessions with the social workers on various issues, and they also sponsored periodic socials for the other children under their care.”

What: Grand opening of “The Legacy of the Hebrew Orphans’ Home”

Where: The Breman, 1440 Spring St., Midtown

When: 6 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 24

Tickets: $150 until Aug. 16, then $180, or $100 for those under 40; jelf.org/breman or 770-396-3080

Birnbrey will be part of a panel discussion moderated by Lewis during the official opening event of the exhibit Thursday, Aug. 24, at 6 p.m. Birnbrey; Caroline Light, an author and historian; Stephen Garber, the son of a Hebrew Orphans’ Home resident; and Sherry Frank, the parent of JELF loan recipients, will discuss stories that are not told in the exhibit.

“That’s why we really wanted to do the event: to bring the exhibit to life,” Lewis said.

Curator Catherine Lewis of Kennesaw State says the goal of the panel discussion Aug. 24 is to bring the exhibit to life.

For Birnbrey, the exhibit and event will connect the past with the future.

“By speaking on the panel, I can express my gratitude and hope that people will realize the good a community can do,” he said.

Lewis also hopes people who attend the exhibit will see the role the entire Atlanta Jewish community had in helping children like Birnbrey.

“I want people to walk out and think: It’s not one person. It’s not three people. It’s hundreds of people that have committed to this and transformed our community,” she said.

Birnbrey hopes that realization will inspire people to continue to support the mission.

“I am convinced, having been in fundraising for approximately 60 years, that people wait to be asked to give and then sometimes get very enthusiastic about what they are doing for the good of the community,” he said.

Although the Jewish community doesn’t have orphans as it did during the late 1800s and early 1900s, when single parents often put children in the home, or during the 1930s and 1940s, when children fled Europe alone, many people still rely on the organization started all those years ago.

“People assume there is not as great a need in the Jewish community now as when we had large waves of Jewish immigrants, or people assume that the problems we hear about in the greater community — alcoholism, drug abuse, deadbeat dads — don’t exist in the Jewish community,” Marianne Garber said.

But Jewish families face the same issues that can make college unaffordable for anyone, she said. “In some ways, I think the need is even greater today.”

After more than 140 years, JELF continues to evolve and reach new goals, and with this exhibit Shulman hopes attendees will get a chance to appreciate the organization’s roots.

“I’m looking forward to having people connect with the history, understand it and walk away with a deeper appreciation of the organization,” she said. “We should be proud as a community that we’ve been helping kids in this community for all these years.”