Articles A Yom Kippur reminder: The idea of debt forgiveness dates at least as far back as the Bible

This Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur mark the start of a Shmita year, a period described in the Torah when creditors were supposed to release debtors from their obligations

Last Updated: Sept. 16, 2021 at 3:41 p.m. ET

First Published: Sept. 15, 2021 at 2:04 p.m. ET

Over the past couple of years, the idea of debt forgiveness — whether for student loans, medical, or rent debt — has gone from radical to relatively mainstream. But as many organizations touting broad-based debt relief will tell you, it’s not a new, revolutionary concept. In fact, it dates back (at least) all the way to the Old Testament of the Bible.

“Every seventh year you shall practice the remission of debts,” the 15th chapter of Deuteronomy reads. “This shall be the nature of the remission: every creditor shall remit the due that he claims from his fellow.”

In the original Hebrew, the word for this remission of debts is Shmita, which literally translates to release. The concept appears elsewhere in the Torah — how Jews refer to the Old Testament of the Bible — as instructions to farmers to give the land a break, letting it lie fallow, every seventh year. As part of the Shmita year, landowners were also supposed to open their fields to their neighbors and the poor and slaveholders were instructed to set their slaves free.

This week’s column seemed like a good time to dig into the origins and impact of Shmita because, according to the Jewish calendar, we’re now at the start of a Shmita year.

Jews around the world marked the beginning of 5782 last week with Rosh Hashanah and on Thursday night, the high holiday period of reflection will close with the end of Yom Kippur. The Shmita year lasts until these holidays take place again next fall.

From utopian to practical

Whereas today, both the wealthy and the less well-off use credit, during the era and society where the Bible is set, loans were typically only used by the poor, said Benjamin Porat, the director of the Institute for Research in Jewish Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“A loan is kind of a mechanism for the rich people to become richer at the expense of the poor people,” Porat said.

Shmita was one of a few ways the Bible tries to correct for this imbalance, Porat said. For example, the Torah prohibits lenders from charging interest.

“Shmita is part of a complex of ideas in the Bible that essentially promote a socioeconomic vision in which people are given second chances to start over again in which they might change their economic and social position,” said Suzanne Last Stone, a professor of Jewish law at Cardozo Law School, Yeshiva University. “It kind of is like a reboot economically.”

‘It kind of is like a reboot economically.’ — Suzanne Last Stone, a professor of Jewish law at Cardozo Law School, Yeshiva University

The vision of society laid out in the Bible is almost utopian, Stone and Porat said. But once rabbis began interpreting the Bible and translating it into a law code in the first century BCE, they developed an approach to Shmita that was less radical and more practical.

“There’s also a sense that you can’t demand too much or humans won’t be able to actually do it,” Stone says.

Indeed, the Jewish sages of the time observed that creditors were hesitant to lend to borrowers in the later years of a Shmita cycle for fear they wouldn’t recoup the funds they lent out. So famed Jewish scholar, Hillel, came up with a workaround, called prozbul.

Creditors would transfer their debts to the court up through the end of the Shmita year, but because the obligation to forgive debts under Shmita only fell on individuals, the court wasn’t obligated to cancel the loans. This created “a legal fiction that allows the creditor to maintain and collect the debt eventually,” Stone said.

Prozbol fits in with the larger approach during the period, known as the Rabbinic Era, in which the sages were concerned with helping the poor, but not necessarily transforming their circumstances as laid out in the Bible, Stone said.

“Cancelling debts is a kind of radical way of treating the poor that allows the poor to really achieve economic independence in the future,” Stone said. Whereas “the charitable alms box that the community runs in the rabbinic period essentially makes sure that the poor will survive but doesn’t demand a level of charity that will enable them to dig out of their hole.”

The idea of Shmita remains influential in Israeli society. Though the debt release portion of Shmita was changed — and arguably watered down — during the rabbinic period, Porat said it still influenced some of our modern approaches to debt and credit.

“Bankruptcy was shaped with some connection to this Biblical idea,” Porat said. Bankruptcy “happens only to specific individuals at very specific circumstances, but the idea that at some point we are releasing the person who can’t pay the debts and opening the new page,” is reminiscent of the goals of Shmita, he said.

In modern Israeli society, the idea of Shmita remains influential, Porat said, noting that people are aware that this year is a special year. Last Shmita cycle, the concept inspired efforts including a time bank where people donated their skills to those in need, a financial recovery program that helped low-income families settle debts, and more. Members of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, invoked the concept in creating a plan to cancel debts of those in financial distress during the last Shmita year.

An ‘opportunity for a societal reset in terms of debt and money’

Outside of Israel, environmental and social justice organizations have also looked to implement the lessons of Shmita. Hazon, a Jewish nonprofit focused on sustainability, launched the Shmita Project in 2007, with the goal of raising awareness about this Jewish Sabbatical tradition, said Sarah Zell Young, associate director of national programs at the organization. In July, Hazon hosted a virtual summit for organizations to discuss ways they could be inspired by Shmita values and they’re highlighting and supporting Shmita-inspired projects around the country.

“It’s an opportunity for a societal reset in terms of debt and money and wealth distribution,” Young said of Shmita. “And we want to bring it back into the conversation.”

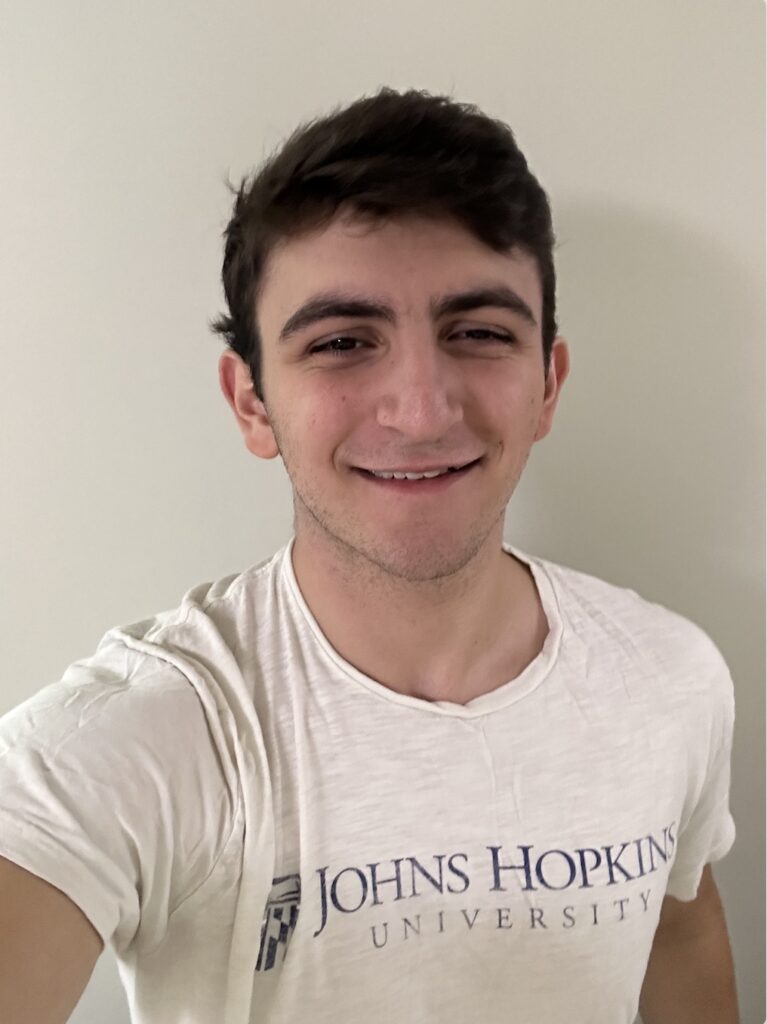

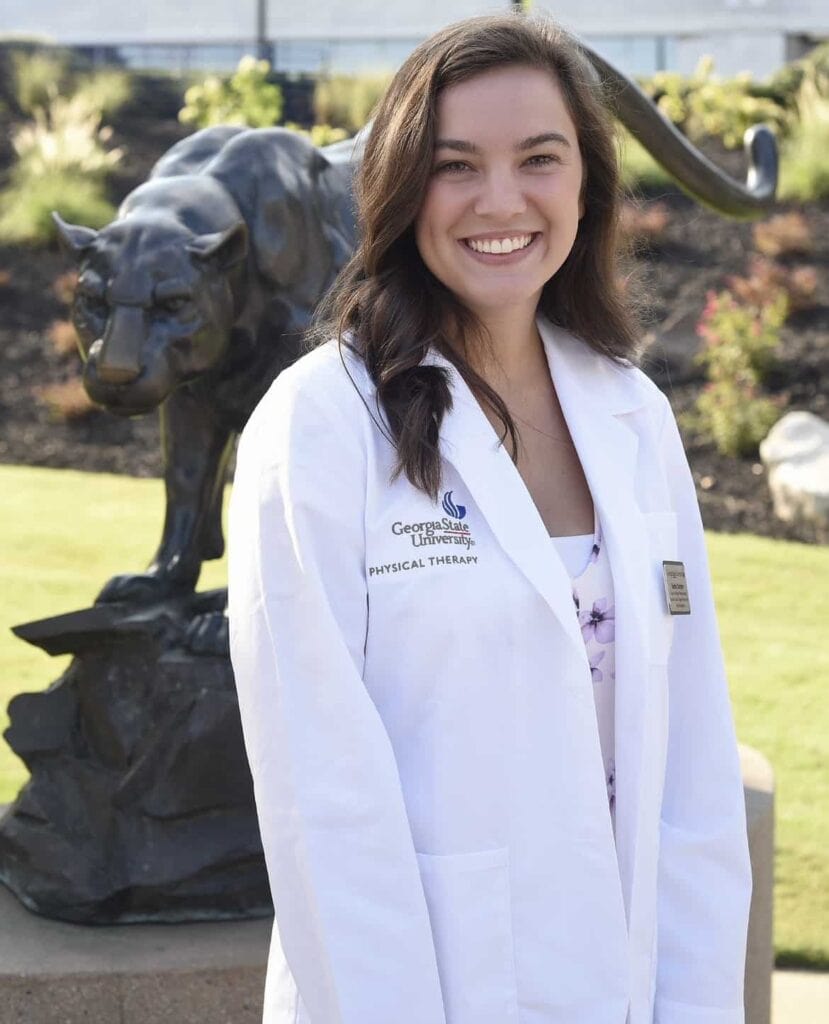

At the Jewish Educational Loan Fund, a nonprofit that provides no-interest loans to low-income Jewish students to attend college or graduate school, leadership is using the Shmita year as an opportunity to provide debt relief for some of its borrowers.

The organization already has some experience with debt cancellation. Last year, a foundation in California was looking to find ways to forgive debt and they provided funding to JELF to relieve some of its borrowers, said Jenna Shulman, the organization’s chief executive officer.

“It was a really life-changing experience for them and for us to be able to deliver the news,” she said. “There was crying and screaming and tears and it was really a shocking experience for me, I didn’t even know that it would be like that.”

For its Shmita campaign, JELF is hoping to raise $300,000 — including $150,000 in matching gifts from two donors — for debt cancellation. Shulman said the beneficiaries of the relief need to have an adjusted gross income of less than $125,000 and a debt-to-income ratio of at least 35%. The organization hopes to be soliciting applications for relief by early 2022, Shulman said. The group expects to cancel the debt of at least 24 borrowers.

Shmita as a check on society

For some activists, Shmita is not only a reminder of what individual organizations can do to create economic and environmental justice, but an opportunity to consider how to reshape society more broadly to achieve those goals.

“While the Bible recognizes that we live in a capitalist society, it also recognizes that if that capitalist society goes unchecked then very bad things are going to happen,” said David Krantz, a doctoral candidate at Arizona State University and co-founder of Aytzim, a Jewish environmental nonprofit. “It needs to be checked and checked on a regular basis.”

Still, one-time debt relief isn’t enough to provide the reset that Shmita promises, he said.

“Yes, we need to release debt, but we need to be thinking also about why people are getting into so much debt and what we can do differently in society to help manage that,” he said.

Debt ‘Jubilees’ also come from the Bible

The Debt Collective, an organization with roots in Occupy Wall Street, has been pushing for debtors, creditors, government officials and others to re-think debt’s role in our society for years with a nod to the biblical concept of the Jubilee, a period of debt forgiveness that occurs every seven Shmita cycles, or once every 50 years.

In 2012, the organization started the Rolling Jubilee, an initiative to buy up medical debt and cancel it, later expanding the concept to student debt from for-profit colleges. Earlier this year, the Debt Collective launched the Biden Jubilee 100, a campaign to push President Joe Biden to cancel all outstanding student debt.

When the group first decided to use the term, some organizers wondered whether it would resonate broadly, said Thomas Gokey, an organizer at the Debt Collective.

“Does anyone even know what the Jubilee is?” is a question Gokey said he remembers organizers discussing. “Would we be losing people, or would this be a chance for people if maybe they haven’t encountered this term before to learn something?”

As part of its work, the organization is thinking through not just cancelling financial debts, but also how society can be reshaped beyond a one-time Jubilee. In the case of student debt, that means revamping the system so that the next generation isn’t burdened with similar challenges, Gokey said, but the changes they’re envisioning are broader and may involve creating different kinds of debts or bonds. For example, taking on the obligation to provide everyone with health care or to pay reparations for slavery, he said.

“The big question that we want to pose to everybody is what debts do we really owe to each other,” Gokey said. “Not which debt your credit card company says you owe. What are your real obligations to people?”